Triangles, Triads, and Challenging Change

I’m intrigued by family systems theory, developed by psychiatrist Murray Bowen and eloquently explained by Roberta Gilbert in her book Extraordinary Relationships. In my photography work, I explore relationships, and I see these dynamics at work all the time.

In family systems theory, there’s a lot of talk about triangles. In music theory, it’s triads. While noodling around on my cigar box guitar recently, a simple chord change revealed a surprising connection between these two different theories that helped me actually hear one of family systems theory’s central concepts.

In simplified terms, family systems theory looks at difficulties expressed in one individual in terms of group dynamics, rather than in terms of that one person having a problem and needing help. Challenging behaviors are seen in the context of an overall group dynamic.

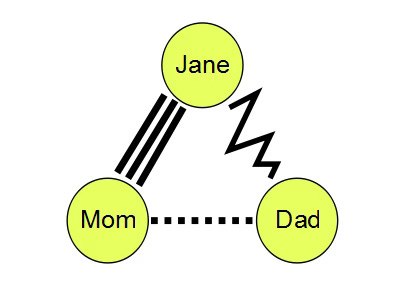

Change within such a system can be very difficult. When two people are experiencing discord or stress or anxiety, they'll often loop in a third person to take on part of their emotional burden. They effectively off-load some of their anxiety to this third person. Once an equilibrium has been arrived at within such a triangle, it becomes difficult for any one person to change their behavior because that change necessitates changes in all the relationships within the group.

A change in one person not only affects three different relationships, but also the overall group dynamic, and the other members of the group might be unwilling or unable to make the necessary adjustments, due to the discomfort involved.

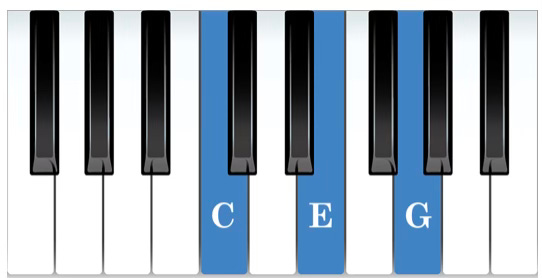

I remember learning how to play a C major chord on a piano keyboard, and how simply and beautifully three notes (C, E and G) relate, how they blend together to make a powerful, pleasing, balanced sound. On the piano, this chord is made up by playing every other white key starting at the C.

I also learned how to turn a C major into a C minor chord by moving my middle finger ever so slightly to the left, changing just the middle note by the smallest increment available, one half-step. C minor provides a very different sound experience. Where the major chord communicates strength, stability and sunshine, the minor chord sounds sad, pensive, cloudy. I thought it remarkable that all this happens just by changing one note, the E, by a tiny amount.

Whenever I sit down at a piano keyboard, I'll play a C major chord and then a C minor chord before I do anything else. Truth be told, there's not much else I can do on a piano keyboard, but this change never fails to fascinate me.

I build my cigar box guitars with three strings, tuned to a major chord (or triad). On them, I can amuse myself for minutes at a time just pedaling back and forth between a major and a minor chord, changing that one note back and forth, one half-step.

I had a revelation about this recently. Applying the lens of family systems theory, I looked at the major/minor shift, not just in terms of changes in one note, but in terms of changes in a whole set of tonal relationships.

In going from a major chord to a minor, the first note hasn't changed, but the relationship between the first note and the second has changed, and the two notes sound very different together. The space between the two notes, the interval, is smaller. Together, they no longer sound as comfortable or settled. They communicate more tension, a little too close for comfort.

The relationship between the middle note and the top note has been affected as well. Those two notes, now farther apart, sound a different interval. There’s more room and less tension.

While we haven’t changed the distance between the first and third note, that relationship is powerfully colored by the changes in the other relationships. When strumming all three notes together, we hear that a greater change has taken place, the result of a shift in the overall dynamic of the system.

The completed triad now creates a minor chord. Where there was sonic sunshine, we now hear clouds.

A suspended fourth (sus4) chord illustrates the same concept, but a little differently, by raising, rather than lowering, the middle note, again by just one half-step. Where the minor chord creates a more somber sound, the suspended fourth creates a feeling of expectation which can be met, settled or resolved by shifting the middle note back down one half-step to the major chord (phew!).

This revelation helps me understand why change is hard, and that this is why, in a family systems approach to problem solving, everyone is part of the process. Though it's tempting to try to solve problems by asking for changes in the one person who seems to be having issues, the individual can’t make a change without affecting the others, creating changes that unsettle the entire system.

While I’ve had an intellectual grasp of family systems theory for years, and felt it in my gut, it wasn’t until this moment of musical insight that I heard it through my ears. Experiencing this theoretical concept through sound opened me up to a more sensory understanding. It also gave me a clue as to how some musical compositions are capable of affecting us on a deep, emotional level.

Just reading this 2 months after you publication, David... perhaps I should have waited till 3! But enjoyed very much, as like everyone, I muddle through my own triads! Thank you.

This is brilliant, David! Love watching the videos... the last one where you put it together moved me...

I’ve been working with a friend who is a master jazz musician and sound healer who recommended a similar exploration to help me shift a tone up and down which corresponded to a deep emotional block... it’s been powerful, gradual and actually joyful to go up and down in the scale and feel my range of freedom expanding.

As a family therapist, I see this dynamic all the time between family members... making slight shifts in the dance... everyone adjusting just a little bit at a time ends up creating massive and lasting change over time...