Neck and Neck

I had lunch with my friend Bruce Roper recently. Bruce is a luthier who builds unusual, one-off acoustic guitars. He also writes songs, sings and records music in his home studio.

Bruce is the only son in a legendary, Chicago-based folk trio called the Sons of the Never Wrong that has been pleasing audiences for over 30 years. In addition to being a builder, Bruce repairs 200 to 300 guitars every year through Chicago’s Old Town School Music Store. He also teaches guitar building.

I was telling him that I'd been thinking about how to get started on my next cigar box guitar, and imagining it would be fun, and maybe funny, to build a solid-body electric guitar around the three-string configuration I favor for strumming chords.

Our conversation turned to neck angles.

When it comes to cigar box lutherie, I'm unschooled and untrained. I’ve been flying by the seat of my pants for a dozen years.

My first few guitars were the more traditional fretless style, for playing with a slide. When I began building guitars with frets, so that I could strum chords, I got in the habit of adding a quarter-inch fingerboard to the neck. This is a common practice. It makes the neck a bit stronger and it also means you don’t have to scrap the whole neck if you botch the fret installation. This appealed to me.

But, I installed the necks so that the fingerboard ended up flush and parallel with the body of the guitar, in this case the lid of the box, which acts as the soundboard.

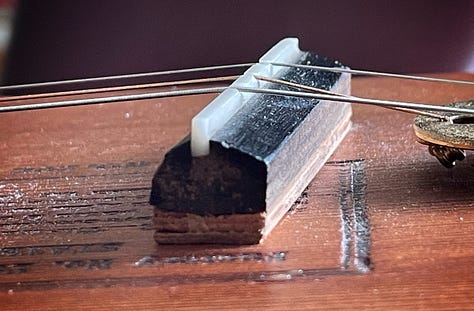

This results in the strings being very close, some might say too close, to the soundboard/lid/body.

My solution for getting those strings up a little higher at the bridge had been to angle the neck back away from the soundboard by a couple of degrees.

The strings still meet the box pretty low, but by the time they reach the saddle/bridge, they're high enough to strum and to finger-pick, and even to accommodate a low-profile pickup.

When I built my first fully acoustic cigar box guitar from an old, solid cedar box, I fitted the neck with the fingerboard proud of the box lid, but I also angled the neck, out of habit and out of not knowing any better. This combination made the strings extra high at the bridge, so I had to build up the bridge and saddle until the strings came up right.

Bruce explained that most Gibson electric guitars have set necks. A set neck is built right into the guitar body and glued in place. Gibson sets most of those necks angled slightly back from the body.

Orville Gibson began as a mandolin builder, making acoustic instruments, mandolins whose arched tops required an angled neck for the strings to be in the right position.

Fender favors bolt-on necks for its electrics, with the fretboard parallel to the guitar top.

Leo Fender was more of an electronics nerd who came to guitar building because of his work in amplification. Leo’s first guitars dispensed with the acoustic model and were solid slabs of wood. He built them with no-nonsense, bolt-on necks, rather than glued-in, set necks, which made his guitars easier and cheaper to produce, repair and customize.

This whole Gibson/Fender split is Guitar Building 101, but I didn't know any of it.

Building for me has been a personal discovery process. I enjoy the unfolding. When I started building, I learned what I could from a single site on GeoCities. YouTube was only five years old, not yet the vast repository of how-to and DIY knowledge that it has since become.

I think my discovery approach is more aligned with the cigar box guitar tradition, and also in keeping with my preference for using traditional hand-tools as much as possible. All that really matters is that my approach suits me. Your mileage, as they say, may vary.

I’m always amazed whenever anyone builds anything. But those who build guitars i find extra amazing...

This is very cool!